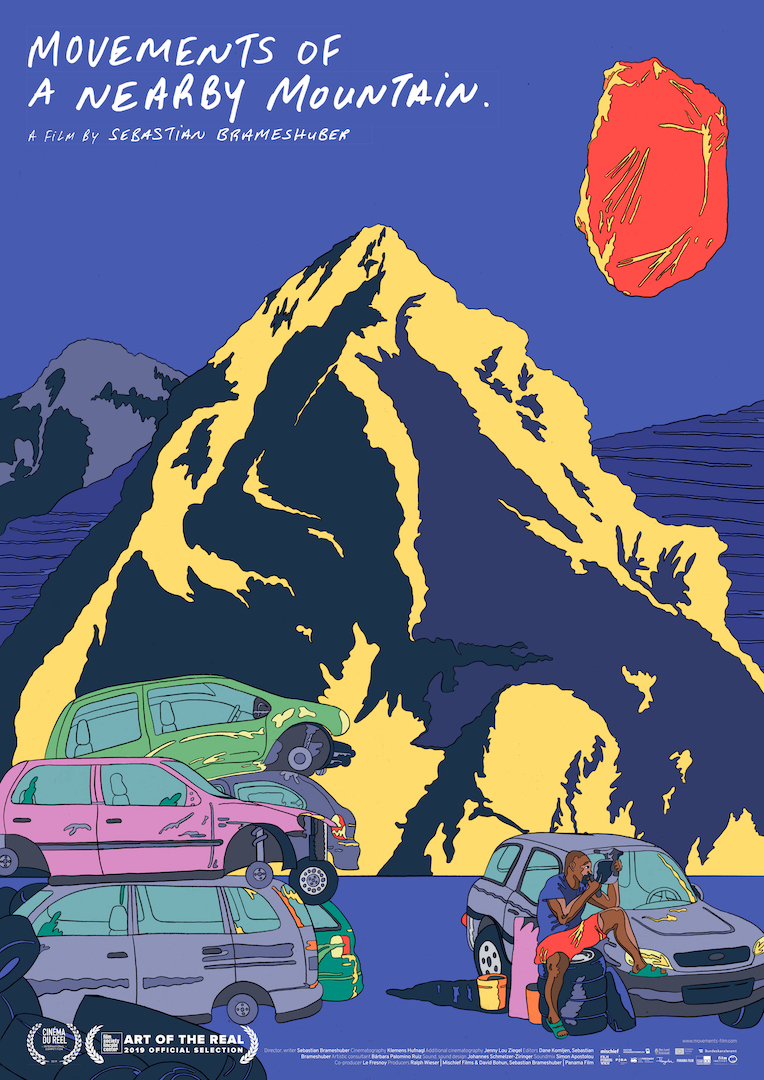

Movements of a Nearby Mountain

Info

Austria/France-2019 | 85min | Shooting format: 4K digital 1:1,77, Super 16mm 1:1,77 | Screening format: DCP 2k, 1:1,85 | Sound: Dolby 5.1 |Languages: Igbo, German, English | Subtitles: English (French available)

Director, writer, co-producer, co-editor: Sebastian Brameshuber | Cinematography: Klemens Hufnagl | Additional cinematography: Jenny Lou Ziegel | Co-editor: Dane Komljen | Additional editing, artistic consultant: Bárbara Palomino Ruiz | Sound, sound design: Johannes Schmelzer-Ziringer | Soundmix: Simon Apostolou | Producers Ralph Wieser Mischief Films, David Bohun Panama Film | Co-producer Le Fresnoy – Studio national des arts contemporains

Beyond the race for technological innovation, cartel-like collusion in the auto parts industry, and the ominous interplay of marketing and emission levels, at the base of the Erzberg mine in Styria (central-western Austria), can be found a part of the automobile market that is not yet so alienated. A Nigerian immigrant in Austria, Cliff buys old cars in order to disassemble and separate their parts in a dilapidated warehouse on the side of a federal highway in the woods before reconditioning them for his former homeland. Carefully distanced and focused, Movements of a Nearby Mountain describes what Cliff ‘s work entails and what it produces in connection to bodies and objects. More than merely documenting his skills, the film weaves together the visible with the invisible and the myths and histories surrounding and pervading the material world: the waterman, who brought people iron for eternity, the promises and mechanisms of the market on two continents of the earth as well as life between these worlds and the end of the chain of exploitation — which is simultaneously its beginning.

DIRECTOR’S NOTE

Movements of a Nearby Mountain is the result of my long-lasting relationship with the film’s main protagonist, Cliff (35), a Nigerian self-taught mechanic who prepares used cars for export to his former homeland, as well as with the site of his workshop. I discovered the location and got to know Cliff and his colleague Magnus in 2011 during the shooting of my film And There We Are, in the Middle, when that film’s teenage protagonists played paintball there. The paintball field has since disappeared, while Magnus quit the business out of exhaustion five years ago.

I was drawn to make this film by Cliff’s optimism, his strong sense of freedom and his self-respect despite his rather uncertain situation. Cliff leads an existence at the fringes of the capitalist system and global trade, where its contradictions and limits become obvious, but where the mighty gravity exerted by its center is still the ruling force. The entire setting, full of traces and memories, is steeped in a feeling of transience.

The ancient factory hall which Cliff has appropriated contains the dilemma of the Anthropocene in a nutshell: the “movements of a nearby mountain”, the deterritorialization and ultimately the finitude of the planet’s resources. Not far from Cliff’s garage operates one of Europe’s oldest and largest ore mines, Erzberg (“mountain of ore”). The legend of its discovery involves the capturing of a water- man, which, in order to regain its freedom, promises “gold for a breath, silver for a lifetime or iron forever”. To me, this promise of eternity is a reminder of an imminent end, or shall we call it: a new beginning?

I was intrigued by the materiality of Cliff’s garage; the richness of its object world that falls onto you from every corner of the workshop, the diverse languages and accents of the visiting clients (and Cliff meeting them halfway), and above all the tangible quality of time. The even, unhurried tempo of Cliff performing his work and moving through space introduces an unearthly rhythm, as if time has a different quality here, as if Cliff’s body movements are being met with a slight resistance, as one would underwater. All of this is amplified by his solitariness.

By recycling patches of Super 16mm footage and sounds which I recorded five years ago for my short film Of Stains, Scrap & Tires, I wanted to make this materiality an integral part of the film, while at the same time introducing an immaterial dimension — Cliff’s memory of the past, of a time when he still shared the space with Magnus, the “blue-collar worker”. A time when Cliff shared, if not abundance, at least dreams of a better future.

THE OBJECTS AND MYTHS OF THE MARKET

Text by Alejandro Bachmann

I.

Beyond the race for technological innovation, cartel-like collusion in the auto parts industry, and the ominous interplay of marketing and emission levels, at the base of the Erzberg mine in Styria (central-western Austria), Sebastian Brameshuber discovers a part of the automo- bile market that is seemingly not so alienated. A Nigerian immigrant in Austria, Cliff buys old cars in order to salvage them in a dilapidated warehouse on the side of a federal highway in the woods. Yet “salvage” hardly seems to describe what Movements of a Nearby Mountain shows us of this work. One would come closer to what Cliff carries out in summer and winter in nearly complete isolation if one were to name each of the procedures one by one — the selection, evaluation, disassembly, ordering, labeling, packing, and reconditioning for the market in his former homeland — that Cliff himself performs. Without false romanticism, the film also depicts (relatively) honest work. How it feels, what happens with breathing and movement, and the relationships between worker and product that emerge from them are soaked up in images that always remain at a slight distance (no silly close-ups of sweaty bodies or fractured cars), expressed in the calm, relaxed, but nevertheless dynamic editing, and conveyed in the concentrated density of the sound. Everything being considered here through images and sounds is to a special degree bound to or drawn from the protagonist’s material world. In this sense, the film is a documentary.

II.

Movements of a Nearby Mountain is however also a film about myths and histories and systems and ideas created by realities (and markets): the block of text at the beginning of the film briefly summarizes how the iron in the Erzberg (literally: ore mountain) has been mined since the Roman era and the legend according to which it will never dry up. Cliff twice tells the myth of the waterman who brings people iron for all eternity — once in German, once in Igbo. Not only is iron, not only are brake disks and spark plugs exported. An idea and a promise are also exported. With each of Cliff ‘s resold cars, Erzberg also comes closer to Nigeria. Behind the visible, physical work, the film reveals a narrative dreaming of the global market: when Cliff disassembles the motor of a chosen vehicle that is elevated in the air by a forklift and encased in plastic wrap, it somewhat resembles a gemstone and a cocoon and the soon to be exported motor becomes a symbol of a wish for the constantly renewed creation of value.

One wants to think that the trip to Nigeria does not feel like a homecoming for Cliff. He even looks isolated in the market and later goes on a walk alone in the woods. Not a return to nature, but rather the feeling of isolation; the presence of animals and insects, the wind and the ground. Pausing, he looks at his phone for a while, just as he did at the beginning of the film. We see an image of his friend Magnus on it who is (probably) sitting on a rock near the warehouse in Styria, a little like a waterman, in blue overalls and with a phone to his ear. Magnus appears again and again during the film. A ghostly presence, we do not hear his foot- steps, but he nevertheless speaks — very concretely — about auto parts and taxi businesses in Nigeria. Stories and thoughts constantly jump out of the documentary observations, incidental and yet insistent, and create connections between the objects and people.

III.

On a diffused, foggy threshold Movements of a Nearby Mountain moves between the material world and the ghosts surrounding it — the market, money, and myths deposited in it. On one hand, the world’s concrete, haptic physicality, the presence in the present and its impermanence, the rust (which is also repeatedly a subject of the minimalistic “poetics of negotiation” between Cliff and occasional buyers who pop up), traces of the neighboring, abandoned paintball field, and the feeling that Magnus was once there, entirely real, as Cliff ‘s friend, brother, or business partner. On the other, the myth of eternity, the legends of never-ending raw materials, and the chain of exploitation derived from them, the suspension of time and space. At the end, the sound of Nigeria’s heat in December is laid over a long, hypnotic phantom ride through a wintry Erzberg landscape, a foggy mountain in the distance. Cliff, the iron, the market — they are always and everywhere together, strangely present, even if they can also hardly be conclusively placed.

(Translated from German to English by Ted Fendt)

“THE ROAD NOW LEADS SOUTH.”

(An Essay on Movements of a Nearby Mountain by James Lattimer)

The tools are rudimentary, but they get the job done, the bread knife, the hammer, the drill and its various attachments. Screws are removed, wires sliced through, and entire sections disassembled and put aside, sometimes with patience, sometimes with brute force. He works alone and it takes time for the individual parts to emerge from the whole, the ones stacked up in the far corner of the warehouse, the bumpers, the exhaust pipes, the tires, like bones scrubbed clean of flesh. When the old engines are hung up to let the oil drain out of them, it’s as if they’re suspended on meat hooks, afterwards they’re wrapped in cling film, although they hardly need keeping fresh. He usually works in silence, except for the few times he hums a song to himself, the tools also bang, metal scrapes across the floor and motors run; every clank echoes. The space is large and the camera is as patient as he is in exploring it, first picking out the different sections of the hall, before stepping out to the forecourt outside, weeds pushing up through the concrete, to the small hut where he cooks, to the bridge where he collects the water from the stream; the steep wooded slope behind the fence is already part of the mountain.

Later on, the view widens, to take in the paintball field, the terraces carved into the rock, some bare, some already green, and the quarry from which iron still flows, just as the water sprite promised it would, albeit without saying in which direction and which form; the road now leads south. Sometimes the trees have leaves and sometimes they don’t, sometimes it’s brighter and sometimes it’s more overcast, but up here the quality of the light hardly seems

to change across the seasons, the window panels on the upper half of the warehouse are milky enough to diffuse the sun’s rays anyway, only adding to the sense that this is a place apart, a separate realm; when he starts talking to himself, about the details of the work, about the paintballers across the way, about Nigeria, it can feel like someone else is there. He does sometimes have visitors, they stop in to buy or sell or both, they talk wear and tear, ages and brands, they haggle, they speak German together, but it’s seldom their mother tongue, just the lingua franca of this realm, of this economy, of the time. Perhaps some of them have come thanks to the cards he leaves tucked into the doors of the parked cars, of which there are far more than people, these are the only moments he leaves the warehouse. When he drives trough the surrounding landscape to distribute them, the light is different, greyer, colder that it is at home, like something dimmed, diminished, nearly used up.

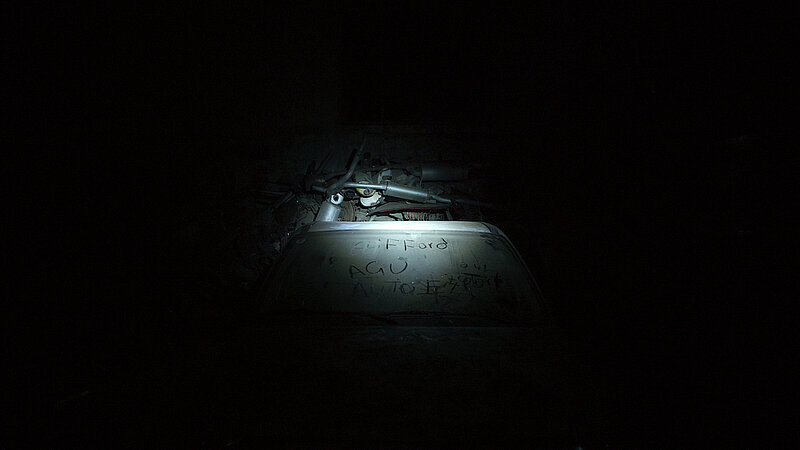

The torch passes over many things in the darkness: names and numbers written in dust on the windscreen, another engine wrapped in clingfilm, the door that leads to the other room, fronds yellow in the light, more vegetation behind, far too green for Austria. The voice, his voice, speaks once in German, once in Igbo: a golden foot, a silver heart, or an iron hat, a mischievous finger pointing to the nearby mountain, an end to enslavement, an echo over the valley, the sound of laughter.

Spieltermine

Austria & Germany: Filmgarten September 27, 2019

US (educational): Aspect Ratio Films

Mexico: Interior XIII

Pressespiegel

«Brameshuber has achieved that wonderfully simple thing where all you have to do is look and see and listen to what is happening on screen in order to get closer to another human being,where in the process of watching everything is revealed, and simultaneously kept mysterious.» mubi

«A film in midstream, neither depraved of strangeness nor of relevance. The mountain’s eden-like purity, the remains of productivist civilisation, a metaphor of recovery, completeness of a film-tableau.» Jacques Mandelbaum, Le Monde

«A film made for the cinema.» Maria Motter, fm4

«A Hanging-Out-Film in its purest form.» Patrick Holzapfel, Jugend ohne Film

«Sebastian Brameshuber’s contemplation on these contrasts and the intimate portrait of one man against the stunning forest backdrop speaks volumes without saying much.» Dustin Chang, Screenanarchy

«A documentary which is ascetic without being dry, simple yet profound and which knows how to impose its own rhythm on proceedings.» Cineuropa

«Movements of a Nearby Mountain has a graceful pace and remarkable elegance.» Interview with Andrea Picard – Cinemascope magazine

«With Movements of a nearby Mountain, Brameshuber succeed to deliver an affectionate portrait. And he accomplishes what a task of film could be: to satisfy the curiosity, without betraying the subject.» ORF

«It’s not a typical social-issues type of documentary, but a profoundly humane one that under the surface of the story about a man and his work implies a whole lot of questions, including such considering race, class, geography, political economics or colonialism. At the same time, Movements of a Nearby Mountain is a beautiful film to look at, thanks to Klemens Hufnagl’s attractive cinematography usually in wide shots and experiments with different formats and granulation. The editing handled by a Bosnian-Serbian slow cinema docu-fiction auteur Dane Komljen is also one of the film’s strong points and it suits the story perfectly. Who would say that scrapping cars by a mountain road would be as meditative as driving them on the same location?» Ubiquarian

«One cannot reduce a film festival like the Diagonale to one single film nor to a single topic, but from Movements of a nearby Mountain emanates a lot in this year’s selection.» Bert Rebhandl, FAQ

«Create a space where the present and the past overlap.» Interview mit Karin Schiefer, AFC

«My film is closer to poetry than to prose» Interview – Cineuropa

«Du déracinement à la reconstruction : formes documentaires de la migration» Academic paper (MSHB Rennes)

Biografie

Sebastian Brameshuber studied scenography at the Vienna University of Applied Arts and cinema at the french audiovisual research center Le Fresnoy – Studio National des Arts Contemporains. Since 2004 his work has been regularly present and occasionally awarded at film and media art festivals such as the Berlinale, Viennale, Cinéma du Réel, FID Marseille, BAFICI, Karlovy Vary FF, Sarajevo FF, EMAF Osnabrueck, Impakt Utrecht, Media Art Friesland, among others. Following Muezzin in 2009 and Und in der Mitte, da sind wir in 2014, Bewegungen eines nahen Bergs is Brameshuber’s third feature-length film.

www.sebastianbrameshuber.com

Festivals & Preise

Cinéma du Réel, Paris | Art of the Real, New York | Diagonale, Graz | Crossing Europe, Linz | DokuFest Prizren | Open City Festival London | Art of the Real Buenos Aires | Hamburg Filmfest | Reykjavik IFF | Nürnberg Human Rights IFF| DocLisboa | Mostra de São Paulo | Ji.hlava | Duisburger Filmwoche | Festival Interférences Lyon | Pravo Ljudski FF, Sarajevo | Camara Lucida, Quito, Ecuador | IDFA Amsterdam | Arsenal Berlin | Mostra de Cine de Lanzarote | Filmer le travail Potiers, France | Ficunam, Mexico | Fünf Seen Festival Bavaria | OneWorld Bucharest | Trento Film Festival | Sofia IFF | FIDBA Buenos Aires | Dokka, Karlsruhe | ZagrebDox, Croatia

Special Screenings: EHESS Paris | Le Fresnoy – Studio national des arts contemporains, Roubaix | Cinéma Odyssée Strasbourg | Anthology Film Archives New York | TIFF Bell Light Box Toronto | Austrian Cultural Forum London | Forum culturel autrichien Paris | Austrian cultural Forum New Dehli | Edimotion, Editing Award, Cologne | Europe on Screen, Indonesia

GRAND PRIX Cinéma du Réel 2019

« Thanks to the elegance of his mise en scène and inventive use of the off-screen dimension, the filmmaker managed to move us with the profound humanity of his protagonists.« , that’s the statement of the jury composed by the new artistic director of the Berlinale, Carlo Chatrian, film director Mahamat-Saleh Haroun, critic Nino Kirtadze and producer Madeleine Molyneaux who attributed unanimously the Grand Prix.

Open City Award, London

About their choice, the jury said that “the winning film exemplifies an assured coming together of form and content to craft an intimate portrait of a character whose daily life illuminates a global conversation about labour, movement and capitalism. From the patient gaze of the camera to the perfectly paced, rhythmic cadence of the edit, there is a precise intentionality in each element of the visual and sonic landscape. This elegant economy of form holds space for the imaginative and poetic dimensions of myth and the tactile materiality of work.” The jury consisted of Karen Alexander (curator), Erika Balsom (lecturer, critic), Lucy Cohen (filmmaker) and Steven Eastwood (filmmaker), and is chaired by Tabitha Jackson, Director of the Documentary Film Program at the Sundance Institute.

Award of the political film, Friedrich Erbert Foundation, Hamburg Filmfest

Excerpts from the Jury statement: « It’s a film which takes you under its spell, that simply makes happy. »

3Sat Dokumentarfilmpreis, Duisburger Filmwoche

“Uprooting, migration, adaptation, life and survival are processes both distant and omnipresent and affect people as well as things. Sebastian Brameshuber lends cinematic form to these movements of thought, demanding a magical materialism that is as unpretentious as it is elaborate.” (An excerpt of the Duisburg jury statement)

Best Cinematography Feature Film (Klemens Hufnagl), Diagonale, Graz

“One man, one space. We almost only see that, a man in a space. And yet – by the tender look, the gentle distance, the quiet fascination – the whole world is in this man and in this space.” The jury was composed of Viennale’s artistic director Eva Sangiorgi, filmmaker Patric Chiha (Brothers of the Night) and film editor Gesa Jäger.

Local Artist Award – Crossing Europe Film Festival Linz

Jury statement: “We wish to honor a film that manages to weave a complex and multilayered web of storytelling through precise and concentrated observations: about movements of people and goods, about economic and ecological cycles in an industry riddled with crisis, and the mythical legends that stoke its flames. Dimensions of a world that are brought down to a human level with a touching portrait, in images that put the focus on the materiality of our present, and at the same time expand our view to those things that lie on the margins of it.”

Wiener Filmpreis – Special Jury Award, Viennale’19

Material

Trailer with English subtitles Youtube Vimeo

Fotos (43Mb), Pressbooklet, EPK, Poster (jpg 17Mb), Interview with the Austrian Film Commission

Educational materials:

Schulmaterialien (Deutsch)

Analyse de séquence – Arrêts sur image | CNC (französisch)

Interviews

“CINEMA AS AN OPEN SPACE INVOLVING THINGS NOT VISIBLE AT FIRST GLANCE.”

Talking to Sebastian Brameshuber about Movements of a Nearby Mountain.

By Alejandro Bachmann

Alejandro Bachmann: Movements of a Nearby Mountain is not your first film dealing with Cliff ‘s work. In 2014, you shot a short film about him, Magnus, and another colleague — Of Stains, Scrap & Tires. If we put the films side by side, there are strong similarities — the subject, in some places the film’s form as well, for example the extended tracking shots from a car when Cliff and his colleagues are looking for vehicles to buy—but also differences — one of the men seems not to be there anymore and in the new film, it is uncertain if Magnus is still there. What changed between the two films — very concretely on location, in reality, if you will, but perhaps also in your view of the topic and then in your search for the form of the film?

Sebastian Brameshuber: Magnus left the export business even before the editing of the short film was finished. It was too stressful for him because there was constantly more competition and the conditions were constantly becoming tougher. In the raw footage for Of Stains, Scrap & Tires, there’s a scene where he sprays over his phone number at the entrance to the warehouse. I found this image very strong: a short, unsentimental gesture with which he closes this chapter in his life. For me, the beginning of a new film was already present in this. I mainly stayed in touch with Cliff, probably also out of a feeling of mutual respect. Cliff and I agreed very quickly that we wanted to make another film together. Since it then took a while to finance this project, our acquaintanceship could turn into friendship. I was impressed by how in spite of all adversity, Cliff continued on with the transcontinental used car business. There are very concrete efforts from the Austrian scrap metal lobby so that the metal — which leaves Austria in the direction of Eastern Europe and the African continent in the form of used cars and spare parts — remains in the country in order to supply their expensively purchased and not very active shredding facilities. Metal recycling is a big business.

But not only did the framework for Cliff ‘s business model change, his immediate surrounding did too. When I visited him again one day in the warehouse, the paintball field had suddenly disappeared and part of the location’s acoustic backdrop along with it. But the traces of the tires stacked on the field for many years were still there, photographic imprints created by the weather, framed by a bit of moss and grass that had grown around them. Impermanence is clearly one of the strongest themes that interested me with Movements of a Nearby Mountain; the different times and temporalities superimposed in this location. Photographic traces of Magnus’ presence in this location also existed in the footage shot for the short film. Looking at it again, I noticed that there were moments with him again and again in which he strangely appears or disappears, like a phantom; a peculiarity that I’ve also often experienced in real encounters with him. Out of this eventually came the idea of giving Magnus an immaterial presence in the film, but with a casualness that also allows for a more material interpretation.

It was actually a lack of gear that led to the short film consisting exclusively of static shots. It was cold and we didn’t have a heated eyecup for the camera, so that the viewfinder would fog up as soon as Klemens Hufnagl tried to shoot handheld. Therefore some of the footage was unusable, for example a scene with Ibolya and Gusti, the junk dealer couple from Hungary. But now they appear twice in Movements of a Nearby Mountain. At that time, we had also already shot with one of the two Bulgarian dealers, but the scene couldn’t be used for the same reason. I found it interesting how the need for used goods being dealt with here is not only in Africa, but also just beyond the Austrian border in Hungary, in further parts of Eastern Europe. So there was also a chance in this location to describe relations in our world with a higher degree of complexity as had been possible in my previous short film.

In Movements of a Nearby Mountain, I also wanted to achieve a higher degree of cinematic complexity, using a more varied formal structure, with a procedural way of working rather than rigor as its most important principle; the “directorial claims”, so to speak, were to be outbalanced by forms of possibilities. The latter should maybe even take preference over the former. I think the meandering quality — already present in the structure of the short film and something that I am in fact striving for — finds a new quality in Movements of a Nearby Mountain, above all in terms of the camera, in relation of the moving to the static shots. In fact, I also found that film was not the right choice for the short in filming this location. The texture of film stock always evokes a nostalgic desire for materiality and tactility and in this case both were already present in abundance: different concrete, wood, glass, and metal surfaces, wood shavings, rust, dust, scratches, dents, splashes of paint. The materiality of film stock actually worked against the materiality of the location. So this time we shot digitally in 4K (although with old Super 16mm Zeiss lenses), allowing Cliff ‘s warehouse to be discovered in slightly surrealistic detail on the movie screen. It sometimes reminds me of those polished and unbelievably detail-rich oil paintings. I think the ghostliness, the immateriality of digital images gets at the material richness of the location very well; there is already a visual tension in the choice of the working tools alone.

A.B.: Let’s stay with the camera briefly. It is interesting that you eschew getting really close, which might have been obvious for some people: Cliff ‘s muscles, the car materials, the rough physicality of the work, these kinds of things offer space for “visual spectacle.” But I like that in Movements of a Nearby Mountain, the camera is in a way unobtrusive, it takes a step back, generates a relaxed balance between Cliff and the space around him. This generates a dis- tance that lends a calm concentration to what is shown. And then there are moments where it formally draws attention to itself, like when Cliff and Magnus are outside looking at the paintball field and it pans back and forth, or also in the three long tracking shots that appear at the beginning of the film, at the beginning of the sequence in Nigeria, and at the end…

S.B.: For Klemens Hufnagl, who was behind the camera, and I, it was never a question of getting closer that way. At the end of each day of shooting, as we looked at the footage, it simply felt right. Movements of a Nearby Mountain is the fourth film we’ve made together, so we’ve developed an understanding and shorthand. Spectacle as a “harvesting” of the most spectacular images, sounds, or also situations has never interested me, rather the truth and poetry that are in the everyday and that are revealed in a particular way in cinema. Here it’s first of all about looking closely and being patient, so two components that are diametrically opposed to spectacle.

At the same time, there is an insane amount to look at and listen to in this film. The pleasure of looking and sensuality definitely have much more meaning here than in my previous films. But of course the camera deals intensely with the overall relations that are revealed in Cliff ‘s solitude in this massive warehouse. The size of the warehouse also contributes strongly to the feeling that Cliff is entirely alone here. That’s also an example of the kind of “truth” cinema can reveal since in this case we are dealing with a kind of mythological framework in the everyday: the one person (man) in a foreign country who dismantles cars with his bare hands in a secluded warehouse in order to then continue on to another continent. I’m overemphasizing to articulate this more clearly. The film is also constantly offsetting this impression. But this in the film and it communicates with our cultural memory.

In the scene where Cliff and Magnus comment on the paintball game, the camera becomes independent for the first and only time in the film; there is no driving or movements of the characters to motivate the camera movement, at this moment it is autonomous, first panning around and finally turning a full 360°. This might be compared to using italics or quotation marks in a text. For me, this is the film’s central scene, in which the past, present, and future appear at once, where the borders between reality and fiction as well as the relationship between time and space are lifted.

The tracking shots have another quality in regards to the camera as the scene I’ve just described because the car is moving and thus the camera along with it. I liked them in the short film already because it is an easy way to establish the off-screen space, which has always been an important component of my films. Besides, there’s a close relationship between cinema and car rides — the view through the windshield, landscape films that one experiences while sitting. I like the interpretation of these as phantom rides, as you expressed it in your essay. If this feeling sets in, then I think that the most important elements I’ve worked and played with in this film, have come together. Not only have my ideas come together, but all of the people who have worked on the film too — over long periods of time or at decisive moments. All of these decisions are ultimately the result of a dialogue, with my co-editor Dane Komljen and the artist Bárbara Palomino Ruiz, Johannes Schmelzer Ziringer, who was responsible for the sound through to the mix with Simon Apostolou, just to mention a few of the most important ones next to the more obvious roles of Klemens Hufnagl and Jenny Lou Ziegel behind the camera.

A.B.: For me, the tracking shots, especially at the beginning of the film just as at the beginning of Of Stains, Scrap & Tires, have another interesting effect that is related to one of the film’s central, if never explicitly formulated subjects: we wonder who is looking? Who is driving through Styria here and in search of what? And then this is resolved when Cliff gets out and sticks his flyer behind a car’s windshield wiper. So one of the film’s main subjects is established in the first shot: whose world are we encountering and how does this world relate to the one that we may usually connect to the scenery of Styria, mountains, long, drawn out streets, and small places?

S.B.: Yeah, although in the short film there are off-screen conversations in almost every car ride because at that time Cliff was not yet going around on his own. Now it is silent, Cliff only once hums and whistles a religious hymn about eternity: “Ebighi-ebi.” The off-screen space is first and foremost visual and when Cliff gets out it becomes clear that this is a searching movement, a searching gaze. I’ve often accompanied Cliff on his drives, during which he has told me that this is the most stressful part of his work because he feels very exposed because of his skin color and reactions to it. The shield between Cliff and the world through which he looks out from inside his protected car conveys something of this feeling, describes a distance, and is perhaps also a kind of a protective membrane. It’s a possibility to subtly describe Cliff ‘s inner life without making him talk explicitly about it. The tracking shots therefore stand in stark contrast to Cliff ‘s everyday life in the warehouse, since he feels extremely comfortable there. I can remember that with the short film, right at the beginning, some people got the sense that Cliff (and his colleagues) were criminals. If both of them had spoken German off-screen and not Igbo and if a white guy had gotten out to look at the car, another impression would likely have arisen. It is already hard enough with texts to control the meaning so that the “right” message comes across. With film, we often talk about visual vocabulary, but the interaction is obviously endlessly more complex. Consequently, my aspiration as a filmmaker is not to convey a certain message, but to make my films open and multifaceted, to complicate things, and to hone in on issues.

A.B.: The relationship to Cliff is not only relevant in regard to his surroundings in Styria, but also in light of you as a filmmaker. At the latest in the scene you described above in which Cliff and Magnus look at the paintball field, we encounter staged images in which both participated and acted. Can you describe a little the relationship during the shooting? I’m also wondering what roll you, your film, and the collaboration have played for Cliff, what does the film mean to him?

S.B.: I’d have a hard time speaking for Cliff or about what the film means to him. I can only speculate about it. In any case, with Nollywood, Nigeria has a very big low-budget motion picture industry and there is probably also a culture of non-professional actors through it. Cliff and Magnus were ready, aside from the documentation, to take part in this “acting” and interestingly were never irritated when I started to talk about the waterman and different levels of time. I found that interesting and thought about it even more later. The concept of time as something linear and forward moving is a European concept that is reproduced in most films. But the medium of film is suited for using this concept more freely, or even to contradict it. There has also been meanwhile a very strict division of the profane everyday and the world of myths that enlightened adults sneer at. At the same time, the need for myths is obviously huge since they even return falsely objectified in the form of conspiracy theories. Cinema can be a free space where, in spite of its connection to a material universe, everything that is not visible at first glance — the “bigger picture,” so to speak — plays a roll.

A.B.: This is also a very nice description of the sense of time that we get in Movements of a Nearby Mountain: on one hand, there is already something like linear time that gives meaning to many of the activities in relation to Cliff ‘s trip at the end to Nigeria. There is a goal, things are moving toward something. And at the same time, there are the confusing changes of season, the absence and presence of the paintball field, and Magnus’ appearing and disappearing. For me, there is a strange mixture of propulsion and calm here that I would ascribe to a place situated between the necessities of the market on one side and the indifference toward it on the other…

S.B.: Cliff leads an existence on the edge of the capitalist system and global trade, where the contradictions and limits of these become blatant, but where the tremendous attraction exerted by their center is nevertheless still the constant, dominating force. A contradictory play between centrifugal and attractive forces: on the one hand, the centrifugal forces of capitalism push a not inconsequential part of the population to the edge of society, on the other hand, there is the attractive force of its center in the form of the prospect of an economic and social ascent. I can imagine that the tension you’re talking about results from this; on the one hand the urge to make money because economic survival depends on it, but on the other hand a certain form of calm because materially speaking there is not (yet) too much to lose. This is constantly shifting, also depending on if it has been a good or a bad day, a good or a bad week. In your essay on the film, you also mention the “poetics of negotiation” For me, there is a related tension in the negotiation scenes as well that come out of the dialectic between necessity and play. In relation to the film’s structure, there is a kind of goal with the business trip to Nigeria. At one point during the editing, I also considered placing this block more centrally in the film. But my co-editor Dane Komljen and I felt that this would throw the relationship between film’s material and immaterial dimensions off balance. Though I could certainly have taken the abstraction of conventional conceptions of time even further. In any case, in Cliff ‘s workshop, there is an almost tangible quality to time because he pursues all of his activities at the same, even tempo. This has sometimes given me the feeling as if the movements of his body were bumping into a slight resistance, as if there were a very subtle slippage in the space-time continuum. His solitude and the vastness of the warehouse obviously contribute a lot to this. Besides, the entire place is pervaded by a foreboding impermanence, by traces and memories, while at the same time not much vanishes, but people do return from memory, things are supplied with a new or an additional use… In Notes on Kafka, Adorno writes: “The resurrection of the dead would have to take place in the auto graveyards.” Godard and Fassbinder read this too. That’s why the showdowns in Sympathy for the Devil: One Plus One (1968) and The Niklashausen Journey (1970) take place in auto scrapyards.

(Translated from German to English by Ted Fendt)

Book

A book is like a splinter.

As image-splinters, the films of Sebastian Brameshuber go deep into human acts and fault lines, showing possible worlds – inhabitable worlds. This book attempts to measure and chronicle them.

ISBN 978-3-200-06634-2

First edition: October 2019

Languages: English, German

Texts: Alejandro Bachmann, Esther Buss, Stefan Grissemann, Eve Heller, Michelle Koch, André Siegers, Claudia Slanar

Editor: Alejandro Bachmann

Available a.o. at Satyr Buchhandlung (Metro Kinokulturhaus, Vienna)

O R D E R

shipping costs Austria: €3,-

shipping cost EU+CH: €6,50

Shipping cost worldwide: €11,-

Price: € 6,00

Paypal or with wire transfer

Ordering: kontakt@lestudio.at